ABSTRACT

Objective: Apart from the counter-regulation of angiotensin II levels in the renin-angiotensin system, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) acts as a receptor for SARS-CoV-2, which is activated by transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) in target cells. Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), an aging-related protein, controls ACE2 transcription in energy stress situations. This study aimed to evaluate the protein expression of ACE2, TMPRSS2, and SIRT1 in the lungs of children, adults, and elderly individuals. Methods: We used immunohistochemistry and software-assisted analysis to evaluate ACE2, TMPRSS2, and SIRT1 protein expression in autopsied lung tissue with minimal histological abnormalities and no clinical diagnosis of pulmonary disease or infection. The study population included 25 children (newborn to 19-year-old), 7 adults (20- to 59-year-old), and 11 elderly individuals (60- to 95-year-old). Of those 43 patients, 19 were female and 24 were male. Results: ACE2, TMPRSS2, and SIRT1 proteins were more expressed in the pulmonary parenchyma of children than in that of adults (p = 0.043, p = 0.008, and p = 0.032, respectively). SIRT1 expression was higher in the alveoli of children than in those of elderly patients (p = 0.008). No sex-based differences were observed. Spearman's correlation coefficient showed that ACE2, TMPRSS2, and SIRT1 expression decreased with aging. Conclusions: ACE2, TMPRSS2, and SIRT1 were more expressed in the lung parenchyma (but not in the airways) of children than in that of older individuals. This could contribute to less severe COVID-19 lung disease in children.

Keywords:

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; TMPRSS2 protein, human; Sirtuin 1; Lung; Aging.

INTRODUCTION In the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) counteracts angiotensin II through its conversion to angiotensin1-7 [Ang (1-7)]. By activating the G protein-coupled Mas receptors, Ang (1-7) stimulates vasodilatory, anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and antiproliferative effects.(1) In animal studies, ACE2 protein lung expression reduces with senescence.(2,3) In human tissues, ACE2 gene activity declines over the life course.(4)

ACE2 gained renewed attention during the COVID-19 pandemic because it is the main receptor of SARS-CoV-2. After binding to ACE2, SARS-CoV-2 is proteolytically activated by transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2), thus facilitating viral entry into target cells, such as type II pneumocytes in the alveoli.(5-9) Although TMPRSS2 function in human physiology is not well known, TMPRSS2 gene expression is stimulated by androgen hormones and is increased in androgen-dependent prostatic cancer.(10)

Differing expressions of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 proteins have been suggested to play a role in the difference in COVID-19 severity between pediatric and older patients. (11,12) However, most studies have analyzed ACE2 and TMPRSS2 transcriptome and genome in lung samples from adults.(13-15) In addition, there are scarce and contradictory data on the expression of ACE2 protein in the lungs of children. Schurink et al.(16) and Silva et al.(17) reported that pediatric lung samples had lower levels of ACE2, whereas Ortiz et al.(18) and Zhang et al.(19) showed that ACE2 protein was more expressed in the alveolar parenchyma of children than in that of adults and elderly individuals.

An important protein linked to lung senescence is sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), which is known to be decreased in elderly individuals when compared with adults.(20) SIRT1 is a histone deacetylase(21) that plays a key role in cell survival. SIRT1 stimulates ACE2 transcription and protein expression under conditions of cell energy stress(22) and could participate in the mechanisms leading to distinct ACE2 expression through the lifespan.

In addition to the discrepant and scarce results regarding ACE2 and TMPRSS2 proteins expression in the lungs of children, there are no data on the expression of SIRT1 in the alveoli of children. Therefore, the present study sought to assess quantitatively ACE2, TMPRSS2, and SIRT1 protein expression in the pulmonary parenchyma and airways obtained by autopsy of individuals of a wide age range. Our results could provide insight into the intriguing differences in COVID-19 lung disease severity among age groups.

METHODS Study population The present study was approved by the Brazilian National Research Ethics Committee (CAAE no. 80420917.4.0000.0065 and CAAE no. 30364720.0.0000.0068) and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Lung samples were obtained from the autopsy archives of the Department of Pathology of the University of São Paulo School of Medicine, located in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. We selected lung tissue samples from the autopsies of 25 children who died between 1998 and 2020. The samples had minimal histological abnormalities and no clinical diagnosis of pulmonary disease or infection. Lung tissue samples from 7 adults (20- to 59-year age bracket) and 11 elderly individuals (60- to 95-year age bracket) whose lungs were normal on histology and who had no history of pulmonary disease were also selected. Adults and elderly patients were nonsmokers, the exception being one adult.

In the group of children, the Brazilian National Research Ethics Committee granted us a waiver of written informed consent because of the impossibility of tracking down the families. We reviewed all available clinical charts and autopsy reports. The lungs of adults and elderly individuals were collected during the coroner’s autopsies, and there were no available clinical charts. A written interview was conducted, and the next of kin consented to donate tissue samples for research, as well as provided information related to the health status of the deceased adults and elderly individuals.

Tissue processing and immunohistochemistry Each patient had 1-4 paraffin-embedded blocks from which 4-µm-thick sections were cut and stained with H&E to analyze sample viability, i.e., the presence of airways and lung parenchyma, and the absence of infection, cancer, and fibrosis. Lung tissue was fixed in 10% buffered formalin, was routinely processed, and was embedded in paraffin.

New 4-µm-thick sections of each selected block were cut and deparaffinized. Slides were stained with the following monoclonal antibodies: anti-ACE2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, mouse, Cat# MA5-31395, RRID:AB_2787031, 1:2,500); anti-TMPRSS2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, rabbit, Cat# ab109131, RRID:AB_10863728, 1:3,000), and anti-SIRT1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Santa Cruz, CA, USA, mouse, Cat# sc-135792, RRID:AB_2188481, 1:200).

Image analysis and quantification All slides were scanned with Pannoramic Viewer software, version 1.15.2 for Windows (3DHISTECH, Budapest, Hungary), and image analyses were performed with Image-Pro Plus 4.5 software for Windows (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA).

For the lung parenchyma, 15 regions of interest per patient were randomly chosen and 333-335 µm of alveolar septum were selected at 400× magnification, totaling 5 mm of alveolar septum analyzed per patient for each antibody. For the airways, the epithelial expression of ACE2, TMPRSS2, and SIRT1 in non-cartilaginous and cartilaginous airways was quantified in a length of at least 3 mm basement membrane per airway type, for each age group.

The lengths of the alveolar septum and airway epithelium were manually demarcated with the software drawing tool. We defined a color range considered positive staining for each antibody and applied it to all cases to calculate the positive area. This standard was applied to the selected area, and the positive stained area was calculated. The positive stained area was normalized to the corresponding alveolar septum or airway epithelium length (µm2/µm).(23)

Statistical analysis Analyses were performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics software package, version 21.0 for Windows (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The data distribution was determined by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test, which showed that our data were not normally distributed. The Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests were therefore used to compare groups. Variables are presented as median and interquartile range. The correlations were analyzed by the Spearman test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

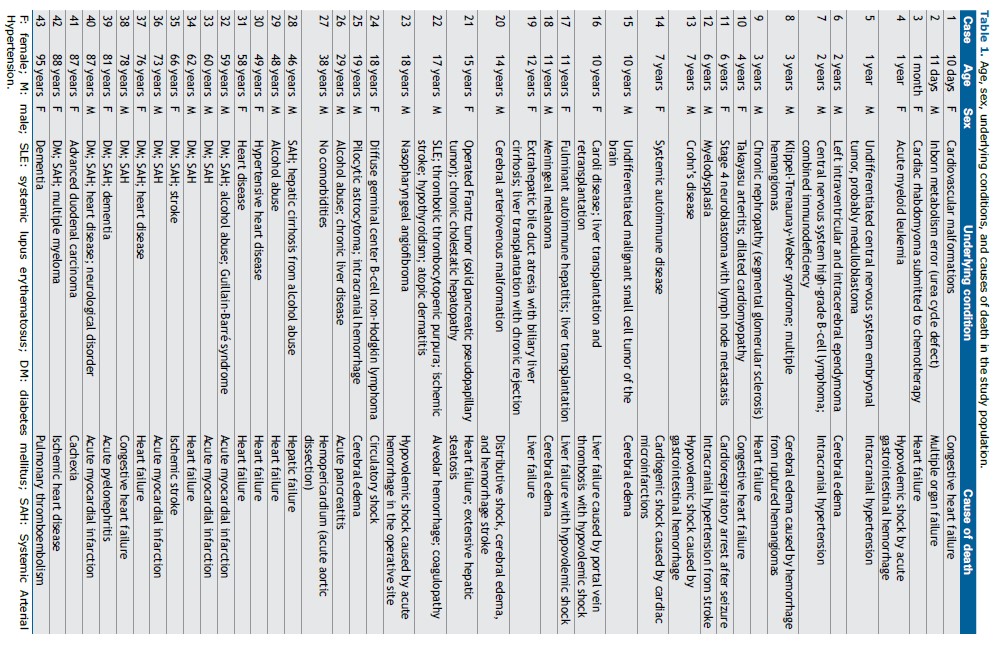

RESULTS The study population consisted of 43 patients (19 Females and 24 Males). The median age of the 25 children (11 F / 14 M) was 7 years (range 0.03-19); the median age of the 7 adults (2 F / 5 M) was 48 years (range 29-59); and the median age of the 11 elderly individuals (6 F / 5 M) was 78 years (range 60-95).

The pediatric group mainly presented with malformations, malignancies, and autoimmune diseases as underlying conditions, and the most common causes of death were cerebral edema and heart failure. The adults and elderly patients had diabetes mellitus and systemic arterial hypertension and died from cardiovascular causes. Table 1 shows the age, sex, underlying conditions, and immediate cause of death of each patient in the study population.

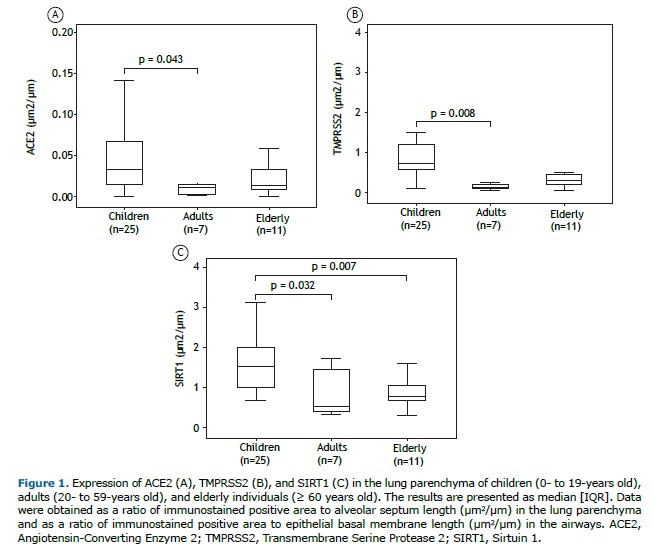

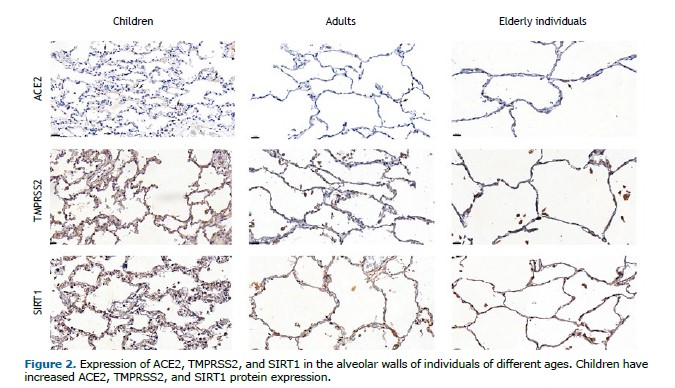

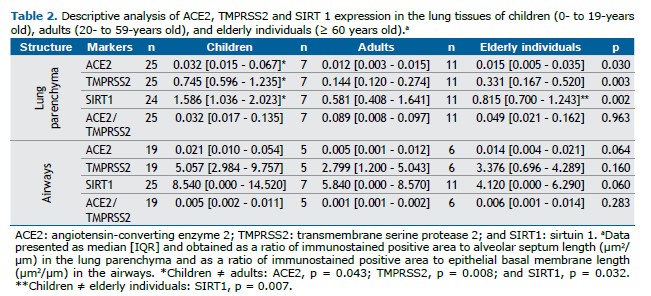

ACE2, TMPRSS2, and SIRT1 protein expression was greater in the alveolar parenchyma of children (p = 0.043, p = 0.008, and p = 0.032, respectively) than in that of adults (Table 2, Figures 1 and 2). In addition, SIRT1 was expressed more in the lung parenchyma of children than in that of elderly individuals (p = 0.007) (Table 2, Figure 1, and Figure 2). There was no statistically significant difference in the expression of ACE2, TMPRSS2, or SIRT1 in the airways among children, adults, and elderly patients (Table 2).

There was no significant difference in ACE2, TMPRSS2, or SIRT1 protein expression between female and male patients in the pulmonary parenchyma or the airways (supplementary material, Table S1). There was no significant difference in ACE2, TMPRSS2, or SIRT1 in the lungs of children when stratified by age (supplementary material, Table S2).

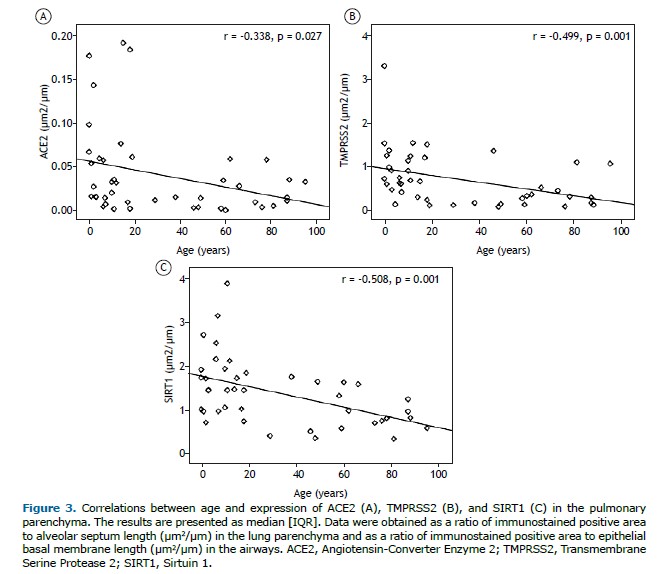

There were negative correlations between age and expression of ACE2 (r = −0.338; p = 0.027), TMPRSS2 (r = −0.499; p = 0.001), and SIRT1 (r = −0.508; p = 0.001) in the pulmonary parenchyma (Figure 3). There were no significant correlations between ACE2, TMPRSS2, and SIRT1 protein levels in the lung compartments.

DISCUSSION In the present study, we investigated the expression of ACE2, TMPRSS2, and SIRT1 proteins in the lungs of deceased individuals without any pulmonary disease, with normal lung histology, comprising the entire human age spectrum. Our results showed that, in the pulmonary parenchyma, these proteins were more expressed in children than in adults, and SIRT1 was more expressed in the pediatric group than in the alveoli of elderly patients. There were no differences in protein expression in the airway epithelium. Additionally, there was no significant difference between females and males or among children separated in different age groups.

Our study is the first to use a semiautomated quantitative method to analyze these proteins and corroborated findings that not only ACE2 but also TMPRSS2 and SIRT1 are more expressed in the lung parenchyma of children. In older individuals, the lower ACE2 levels, by amplifying angiotensin II action, supports pathological processes such as endothelial dysfunction, thrombosis, deleterious inflammation, oxidative stress, and vasoconstriction.(1) When the SARS-CoV-2 envelope fuses with a cell membrane, the extracellular component of ACE2 is internalized and inactivated, thus downregulating this protein.(24) Although counterintuitive, while acting as a receptor for virus entry, the higher expression of membrane-bound ACE2 in alveolar epithelial cells could also protect against RAS system imbalance,(25) which could contribute to the worsening of lung injury.

Viral pneumonia is one of the causes of severe ARDS, and imbalance of the RAS system is part of the pathophysiology of ARDS. Accordingly, ACE2 knockout mice develop more severe ARDS when subjected to lung injury caused by acid(26,27) and when infected with respiratory syncytial virus.(28) It has been suggested that the upregulation of ACE2 could reduce the ARDS-related lung injuries caused by RAS dysregulation.(26,29)

Factors other than ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expressions are also likely to play a significant role in protecting children against more severe COVID-19. Among these factors, greater effectiveness of nasal mucosal innate immunity against SARS-CoV-2 in children(30) could prevent the arrival of a significant amount of virus deep in the lungs, which has been associated with disease severity. Hofstätter et al.(31) also suggested that the respiratory physiology of children provides further protection against effective aerosol SARS-CoV-2 inoculation in the lower respiratory tract.

Interestingly, in the airways there was no difference in ACE2, TMPRSS2, or SIRT1 expression, suggesting that these proteins in these lung structures play no age-related role in possibly defending against or facilitating infection by viruses such as SARS-CoV-2.

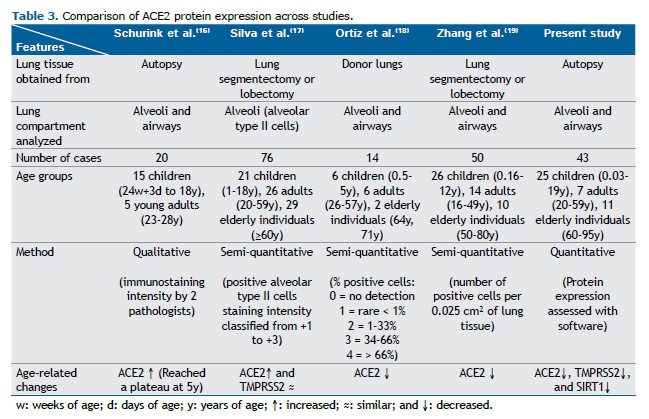

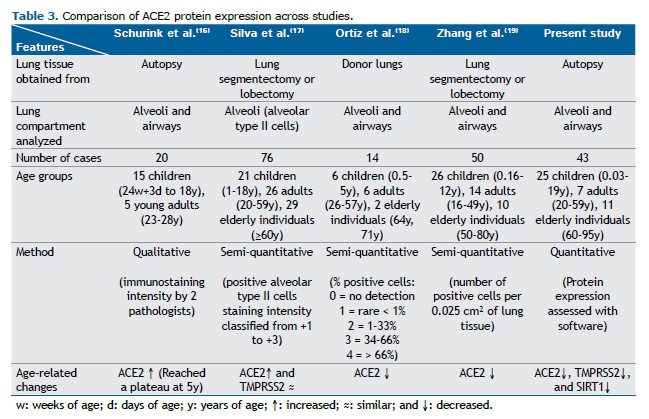

One of the initial hypotheses for COVID-19 being frequently more severe in adults than in children was that the latter could express less ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in the respiratory tract than older individuals.(11,12) This was not confirmed in our results. Nevertheless, studies have shown conflicting results (Table 3).(16-19)

Schurink et al.(16) qualitatively evaluated ACE2 immunostaining intensity in the alveoli and airways of lungs from 15 children (from fetuses to adolescents) and 5 young adults and showed that ACE2 expression was lower in younger children and increased until reaching a plateau at the age of 5 years. Silva et al.(17) analyzed the percentage of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 staining positivity in alveolar type II cells in the lung parenchyma of 21 children, 26 adults, and 29 elderly individuals, classifying the staining intensity from +1 to +3. The study revealed that ACE2 was less expressed in the alveoli of children than in those of adults and elderly individuals, and TMPRSS2 was not different among age groups.(17) In contrast, Ortiz et al.(18) graded the percentage of lung ACE2-positive cells and showed that this protein was more expressed in the lungs of 6 children than in those of 8 adults/elderly patients. Zhang et al.(19) quantified the number of ACE2-positive cells per 0.025 cm2 of lung tissue in 26 children under 12 years of age and 24 adults/elderly individuals. This protein was more expressed in the lungs of children and declined progressively when the samples were grouped as 0-10 years of age, 10-50 years of age, 50-60 years of age, 60-70 years of age, and > 70 years of age, with no difference between the first two groups.(19)

We detected increased levels of TMPRSS2 in the lung parenchyma of children. Although TMPRSS2 also acts as a primer for human metapneumovirus(32) and human parainfluenza virus,(33) viruses responsible for important respiratory infections, there are limited data on this protein expression in lung tissue. Regarding COVID-19 severity, TMPRSS2 activity was supposed to assist explaining the differences between sexes,(34) but we found no differences between female and male individuals in our results.

The present study is the first to analyze SIRT1 in the lungs of children. We found that SIRT1 was more expressed in children than in adults and elderly individuals. This sirtuin amplifies ACE2 transcription and protein expression and is upregulated under energy stress,(22) as occurs in ARDS. Furthermore, there are several pathways in which sirtuins appear to participate in host defense against viral infection, including against SARS-CoV-2 disease. Sirtuins are known to upregulate nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), a molecule with important antioxidant properties,(35) and other studies have shown decreased levels of NRF2 in children during viral respiratory infections.(36,37) Sirtuins also have antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects by promoting cell autophagy and inhibiting the activation of the nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeat, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLPR3) inflammasome.(38) The SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural protein 14 (NSP14) interacts with SIRT1, inhibiting its ability to activate the NRF2/HMOX1 pathway.(35) It is likely that the increased levels of SIRT1 in the lung parenchyma of children may be another protective factor in modulating COVID-19 severity.

Our study has several limitations. First, the small sample size prevented us from addressing all possible confounding factors, such as the underlying diseases. However, it is particularly challenging to find near normal lung tissue obtained from autopsy. Previous studies have also reported a limited number of samples, reinforcing the difficulty in obtaining nondiseased tissue.(16,18)

Second, a decay in antigenicity through time can be observed in human tissue embedded in paraffin. (39) In our study, the lung tissue from children had been preserved in paraffin for longer periods than had those from adults and elderly individuals. However, since we described an increased expression of ACE2, TMPRSS2, and SIRT1 in children, a possible decrease in antigenicity would have even strengthened our results. In addition, tissue samples from our autopsy archives are preserved by rigorous control of humidity and temperature, and we used antigen retrieval methods during immunohistochemical staining to address the issue of antigen decay.

Third, we have not studied COVID-19 cases for this research, because fortunately we did not have a considerable number of deaths from COVID-19 pneumonia among children in our hospital. Although it might be difficult to compare our data with those from other studies, we quantitatively analyzed ACE2, TMPRSS2, and SIRT1 proteins in individuals of a wide age range, and this may have led to more robust results.

In summary, our study analyzed the entire human age spectrum and showed that children without pulmonary disease have more membrane-bound ACE2, TMPRSS2, and SIRT1 protein levels in the alveoli. It is likely that the putative protective effects of ACE2 and SIRT1 against lung injury, together with a more competent innate immune system in the upper airways, may have fortunately contributed to less severe COVID-19 lung disease in children, even in the prevaccine era.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to thank Bruna da Silva Martins (archival management specialist) and the technicians at the histology and immunohistochemistry laboratories for their essential work.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT All data and material related to this study are available from the corresponding author on request (anacarolinalamounier@alumni.usp.br).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS ACAL participated in the selection of pediatric samples; analyzed images of samples immunostained for ACE2 and TMPRSS2; assisted in performing the statistical analysis; and drafted the manuscript. FCLF participated in the selection of adult and elderly samples. GRJ analyzed images of samples immunostained for SIRT1. NSXC assisted in sample selection; assisted in performing histological and immunohistochemistry quality control; and performed the standard analysis of the sample images. JMB performed the statistical analysis. LVRFSF conceived the study and was involved in its design and coordination; and drafted and revised the manuscript. TM conceived the study; participated in its design and coordination; performed histological and immunohistochemistry quality control; and drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST LVRFSF has received grants and personal fees from Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, OMRON Healthcare, and AbbVie, as well as grants from FAPESP, Fundación INFANT, Timpel Medical, and Diagnostics of America (Dasa), outside the submitted work. The remaining authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES 1. Santos RAS, Sampaio WO, Alzamora AC, Motta-Santos D, Alenina N, Bader M et al. The ACE2/angiotensin-(1-7)/MAS axis of the Renin-Angiotensin System: Focus on Angiotensin-(1-7). Physiol Rev. 2018;98(1):505-553. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00023.2016

2. Xudong X, Junzhu C, Xingxiang W, Furong Z, Yanrong L. Age- and gender-related difference of ACE2 expression in rat lung. Life Sci. 2006;78(19):2166-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2005.09.038

3. Shahbaz S, Oyegbami O, Saito S, Osman M, Sligl W, Elahi S. Differential effects of age, sex and dexamethasone therapy on ACE2/TMPRSS2 expression and susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1021928. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1021928

4. Chen J, Jiang Q, Xia X, Liu K, Yu Z, Tao W, et al. Individual variation of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 gene expression and regulation. Aging Cell. 2020; 19(7). https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.13168

5. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271-280.e278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052

6. Walls AC, Park Y-J, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181(2):281-292.e286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058

7. Zhou P, Yang X-L, Wang X-G, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270-273. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7

8. Jackson CB, Farzan M, Chen B, Choe H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23(1):3-20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-021-00418-x

9. Pinto AL, Rai RK, Brown JC, Griffin P, Edgar JR, Shah A, et al. Ultrastructural insight into SARS-CoV-2 entry and budding in human airway epithelium. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1609. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29255-y

10. Lucas JM, Heinlein C, Kim T, Hernandez SA, Malik MS, True LD, et al. The androgen-regulated protease TMPRSS2 activates a proteolytic cascade involving components of the tumor microenvironment and promotes prostate cancer metastasis. Cancer Disc. 2014;4(11):1310-1325. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-1010

11. Zimmermann P, Curtis N. Why does the severity of COVID-19 differ with age?: Understanding the mechanisms underlying the age gradient in outcome following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41(2):e36-e45. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000003413

12. Rotulo GA, Palma P. Understanding COVID-19 in children: Immune determinants and post-infection conditions. Pediatr Res. 2023;94(2):434-442. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02549-7

13. Bunyavanich S, Do A, Vicencio A. Nasal gene expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in children and adults. JAMA. 2020;323(23):2427-2429. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.8707

14. Wang A, Chiou J, Poirion OB, Buchanan J, Valdez MJ, Verheyden JM, et al. Single-cell multiomic profiling of human lungs reveals cell-type-specific and age-dynamic control of SARS-CoV2 host genes. Elife. 2020; 9:e62522. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.62522

15. Muus C, Luecken MD, Eraslan G, Sikkema L, Waghray A, Heimberg G, et al. Single-cell meta-analysis of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes across tissues and demographics. Nat Med. 2021;27(3):546-559. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-01227-z

16. Schurink B, Roos E, Vos W, Breur M, van der Valk P, Bugiani M. Ace2 protein expression during childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood. Pediatric and Developmental Pathology. 2022; 25(4):404-408. https://doi.org/10.1177/10935266221075312

17. Silva MG, Falcoff NL, Corradi GR, Di Camillo N, Seguel RF, Tabaj GC, et al. Effect of age on human ACE2 and ACE2-expressing alveolar type II cells levels. Pediatr Res. 2023;93(4):948-952. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02163-z

18. Ortiz ME, Thurman A, Pezzulo AA, Leidinger MR, Klesney-Tait JA, Karp PH, et al. Heterogeneous expression of the SARS-Coronavirus-2 receptor ACE2 in the human respiratory tract. EBioMedicine. 2020;60:102976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102976

19. Zhang Z, Guo L, Huang L, Zhang C, Luo R, Zeng L, et al. Distinct disease severity between children and older adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impacts of ACE2 expression, distribution, and lung progenitor cells. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(11):e4154-e4165. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1911

20. Barnes PJ, Baker J, Donnelly LE. Cellular senescence as a mechanism and target in chronic lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(5):556-564. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201810-1975TR

21. Grabowska W, Sikora E, Bielak-Zmijewska A. Sirtuins, a promising target in slowing down the ageing process. Biogerontology. 2017;18(4):447-476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-017-9685-9

22. Clarke NE, Belyaev ND, Lambert DW, Turner AJ. Epigenetic regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) by SIRT1 under conditions of cell energy stress. Clin Sci (Lond). 2014;126(7):507-516. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20130291

23. Buttignol M, Pires-Neto RC, Rossi E Silva RC, Albino MB, Dolhnikoff M, et al. Airway and parenchyma immune cells in influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viral and non-viral diffuse alveolar damage. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):147. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0630-x

24. Lu Y, Zhu Q, Fox DM, Gao C, Stanley SA, Luo K. SARS-CoV-2 down-regulates ACE2 through lysosomal degradation. Mol Biol Cell. 2022;33(14):ar147. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E22-02-0045

25. Verdecchia P, Cavallini C, Spanevello A, Angeli F. Covid-19. Hypertension. 2020;76(2):294-299. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15353

26. Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, Huan Y, Guo F, Guan B, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436(7047):112-116. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03712

27. Kuba K, Yamaguchi T, Penninger JM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in the pathogenesis of ARDS in Covid-19. Front Immunol. 2021;12:732690. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.732690

28. Gu H, Xie Z, Li T, Zhang S, Lai C, Zhu P, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 inhibits lung injury induced by respiratory syncytial virus. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):19840. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19840

29. Gheware A, Ray A, Rana D, Bajpai P, Nambirajan A, Arulselvi S, et al. ACE2 protein expression in lung tissues of severe COVID-19 infection. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):4058. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07918-6

30. Wimmers F, Burrell AR, Feng Y, Zheng H, Arunachalam PS, Hu M, et al. Multi-omics analysis of mucosal and systemic immunity to SARS-CoV-2 after birth. Cell. 2023;186(21):4632-4651.e4623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.044

31. Hofstätter N, Hofer S, Duschl A, Himly M. Children’s privilege in COVID-19: The protective role of the juvenile lung morphometry and ventilatory pattern on airborne SARS-CoV-2 transmission to respiratory epithelial barriers and disease severity. Biomedicines. 2021;9(10):1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9101414

32. Shirogane Y, Takeda M, Iwasaki M, Ishiguro N, Takeuchi H, Nakatsu Y, et al. Efficient multiplication of human metapneumovirus in vero cells expressing the transmembrane serine protease tmprss2. J Virol. 2008;82(17):8942-8946. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00676-08

33. Abe M, Tahara M, Sakai K, Yamaguchi H, Kanou K, Shirato K, et al. TMPRSS2 is an activating protease for respiratory parainfluenza viruses. J Virol. 2013;87(21):11930-11935. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01490-13

34. Okwan-Duodu D, Lim EC, You S, Engman DM. TMPRSS2 activity may mediate sex differences in COVID-19 severity. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00513-7

35. Zhang S, Wang J, Wang L, Aliyari S, Cheng G. SARS-CoV-2 virus NSP14 impairs NRF2/HMOX1 activation by targeting Sirtuin 1. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022;19(8):872-882. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-022-00887-w

36. Sorrentino L, Toscanelli W, Fracella M, De Angelis M, Frasca F, Scagnolari C, et al. NRF2 antioxidant response and interferon-stimulated genes are differentially expressed in respiratory-syncytial-virus- and rhinovirus-infected hospitalized children. Pathogens. 2023;12(4):577. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12040577

37. Gümüş H, Erat T, Öztürk İ, Demir A, Koyuncu I. Oxidative stress and decreased NRF2 level in pediatric patients with COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2022;94(5):2259-2264. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27640

38. Rossi GA, Sacco O, Capizzi A, Mastromarino P. Can resveratrol-inhaled formulations be considered potential adjunct treatments for COVID-19? Front Immunol. 2021;12:670955. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.670955

39. Combs SE, Han G, Mani N, Beruti S, Nerenberg M, Rimm DL. Loss of anti-genicity with tissue age in breast cancer. Lab Invest. 2016;96(3):264-269. https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2015.138

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket